‘Objective Allusions and Subjective Realities. Place in the work of Andrea Hamilton’ by Anthony Downey

‘Strange Seas’ by Ben Eastham

‘The Fugitive and Eternal’ by Jay McCauley Bowstead

‘The Appreciation of the Real’ by Laura Valles

THE FUGITIVE AND ETERNAL

Jay McCauley Bowstead

Royal College of Art,M.A. in Critical Writing

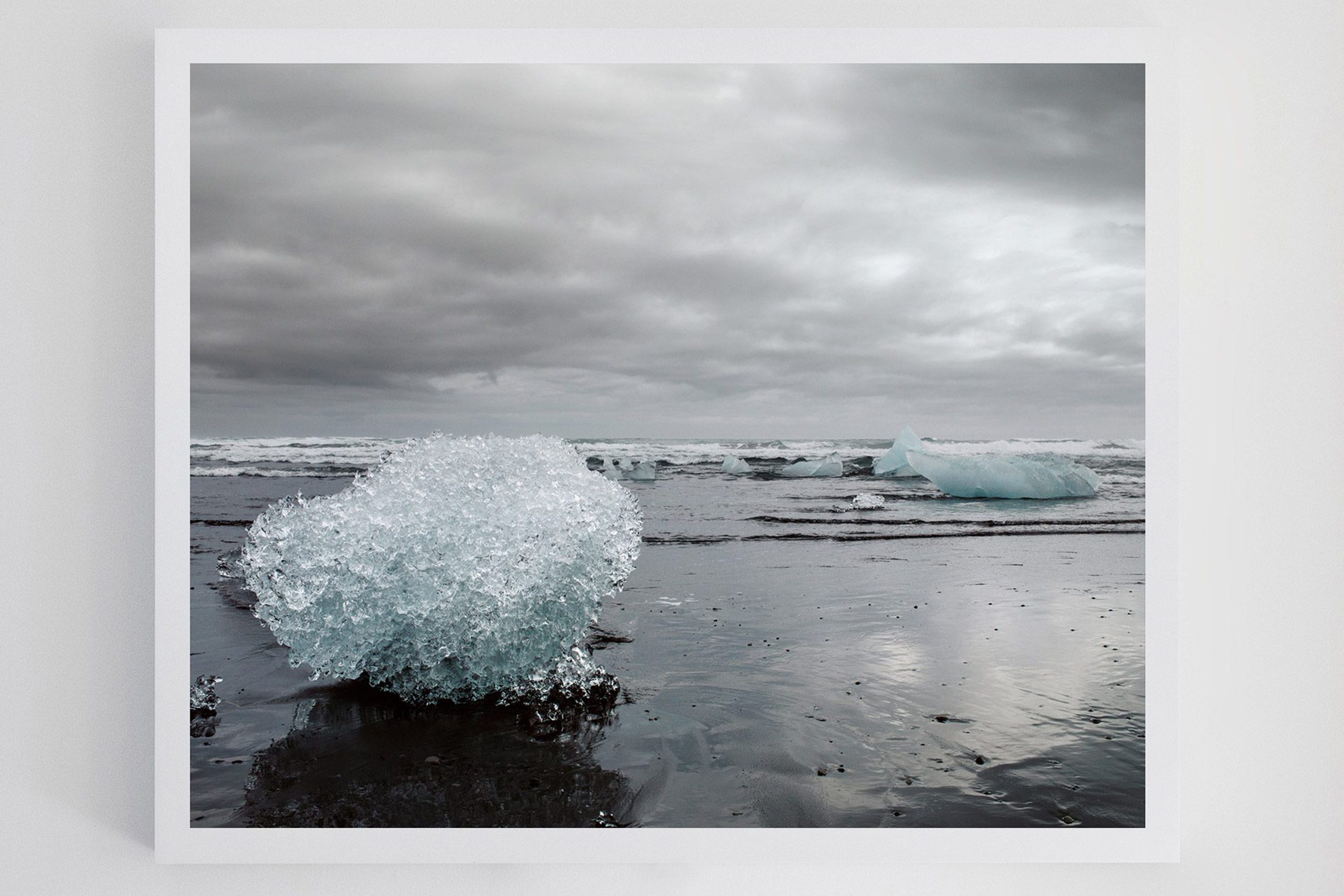

A boulder of intense cobalt-turquoise sits in a landscape of dark glossy sand; to its right another boulder less vivid in its refracted colour; above them a low grey-violet sky; beyond a body of water. The myriad faceted surfaces of these crystalline structures along with their glowing luminescence lend them an uncanny, supernatural presence: beneath the sober sky they seem to emanate light, as if the icebergs – for that is what they are – rather than a distant sun had illuminated the scene. The dips, depressions and sparkling peaks of the boulders mirror the froth of the surf beyond, yet in their fragility – brittle and bright – they seem to be of a different element, a natural gem or the work of some perversely talented Bohemian glassmaker.

The photographs of Andrea Hamilton’s Luminous Icescapes series possess a vitreous quality that goes beyond the inherent glassiness of ice, speaking of the alchemical nature of the frosty terrain she surveys. Here, in a study of light and of form, Hamilton has created images that are wet, reflective and faceted, that hover between representation and abstraction, between land and sea, and between solid and liquid. Sky, rock, shingle and earth fade into one another, a vista of desaturated greys punctuated by gleaming crystalline structures. Like glass, these images embody a simultaneous beauty, danger, and fragility.

Like the medium of photography itself, ice has the ability to capture a moment in time, a wave suspended in its arcuate passage, ephemeral forms of froth and bubbles acquiring an apparent permanency. To capture a moment is also to transform it, to radically alter its material nature, and in this way, Luminous Icescapes is a body of work that not only contemplates unique, breathtakingly beautiful, frightening and alien landscapes, but also engages profoundly with photography as an artistic practice.

In her seminal text On Photography Susan Sontag explores the notion of the photographic image as an emotive encounter:

‘Photographs – especially those of people, of distant landscapes and faraway cities, of the vanished past – are incitements

to reverie.’ 1

This idea of artistic appreciation as reverie has antecedents in Romanticism and in the notion of the sublime, most notably developed and codified by Emmanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgement (Kritik der Urteilskraft)2 of 1790. The work of nineteenth century artists including Constable, Turner and Caspar David Friedrich, which emphasised the wildness and beauty of nature, was at least in part

a reaction to the encroaching industrialisation and urbanisation of Europe, that is, a reaction to the loss of wilderness. And for Sontag, writing in the 1970s, this sense of the fugitive, of the continual upheaval and flux of late modernity, and perhaps most significantly of loss, is felt even more strongly:

‘The beautiful subject can be the object of rueful feelings, because it has aged or decayed or no longer exists.’ 3

In this way, the conscious application of beauty and of its emotive power can be considered a critical act. Hamilton’s work gestures to light, surface and reflection but also to depth. Notions of preciousness permeate the images of Luminous Icescapes in

which ice is transfigured into jewels and cut crystal, but we are

also aware that these icy structures exist beyond their photographic representations. For all their monumentality they are vulnerable and contingent, caught in a moment of melting, fracturing, depleting, returning to the ocean perhaps to be reborn. By emphasising the luminescence and miraculousness of the ice, alongside its fragility, Hamilton speaks of contemporary anxieties surrounding our changing natural world: how much do we value the frozen environments that bore these sparkling, unownable, impermanent jewels that she describes as ‘the Arctic’s solitaire diamonds’?