Mauve | Physis: How colour comes from nature

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense

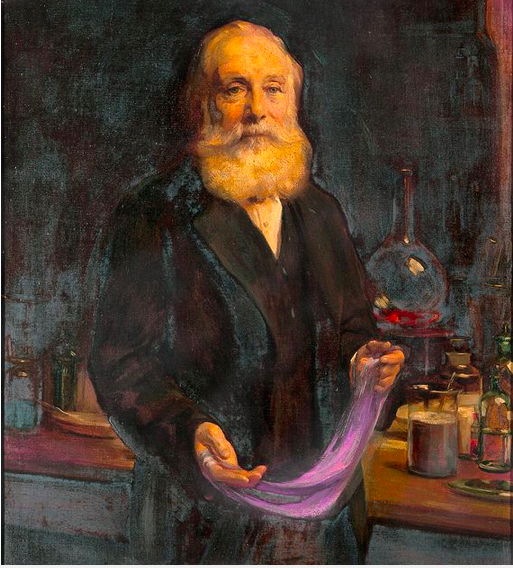

Sir William Henry Perkin by Sir Arthur Stockdale Cope, 1906

© National Portrait Gallery

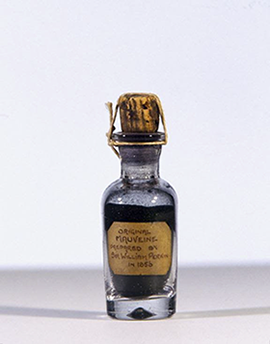

It takes a certain kind of mind to see light in the shadows. One such mind not only changed fashion forever but the course of chemistry itself. In 1856, during the worst outbreak of malaria in Europe, 18-year-old William Henry Perkin was ensconced in his makeshift attic laboratory, trying to extract quinine from the murky byproduct of gas lighting – coal tar. He was the youngest student at the newly-established Royal College, under professor August Wilhelm Hoffmann, a pioneer of organic chemistry who had discovered aniline: an oily, clear liquid which forms an astonishing range of chemicals when mixed and heated with other elements. Perkin failed to create quinine, but he noticed a reddish powder in his black sludge. He experimented further and to his delight produced a livid purple liquid, which he would call mauveine. He repeated the process with, “A different base of more simple construction, viz. aniline, and… obtained a perfectly black product, and when digested with spirits of wine gave the mauve dye.” By dipping a piece of silk into the beaker, Perkin discovered that he had created a wash-proof colour – one that became the first commercial aniline dye.

William Perkin’s original Mauveine dye

© Science Museum London

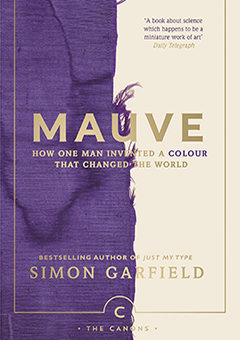

In natural chemistry purple denotes organic chemicals – lavender and the delightfully textured floss flower both repel mosquitoes due to a chemical called coumarin, also present in cinnamon trees, whose young leaves have a pink-mauve hue. However, Perkin’s simple experimentation, described by his biographer Simon Garfield as, “An enquiring mind in an unsupervised laboratory”, went far further. He created a chemical stepping stone which led to a cure for tuberculosis by Nobel Laureate Robert Koch, who discovered its bacillus by dying the spit of a patient; Walter Fleming used it to colour cells and study chromosomes. Aniline could also be used as an analgesic and antiseptic: Paul Ehrlich, the pioneer of chemotherapy, modified the new dyes and developed a range of drugs that saved millions of lives. Little wonder Garfield titled his biography Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour That Changed the World.

Mauve: How one man invented a colour that changed the world.

Simon Garfield © Canongate Books

It was the first time a purple had been made in hundreds of years. When Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453 the secret to the most royal of hues, Tyrian purple, was lost. A dyestuff reserved exclusively for rulers, first Cleopatra and Caesar, then the Pope, it was infinitely more costly than its weight in gold. Extracted from least sexy of sources – the hypobranchial glands or mucus sac of a sea snail – more than 250,000 Murex Brandaris or Thais Haemastoma were needed to make one ounce; getting the colour to adhere to clothing was a foul stinking process.

Empress Eugénie, 1854,

Franz Xaver Winterhalter

© The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

At first, Perkin called his discovery Tyrian purple but heard that a new colour, derived from the mallow plant, had taken hold of the public’s imagination: mauve. Princess Eugenie, a renowned beauty and wife of Napoleon III, who was convinced the colour perfectly matched her eyes, had sparked a fashion craze. The demand encouraged Perkin to explore how to produce it on a large scale, and with no known method (mordant) for fixing aniline dyes to fabric, let alone any existing technology to extract the colour in industrial quantities, the entire enterprise depended on his instinct and ability. Joining with his father and brothers to create Perkin and Sons Ltd, they designed their own distilling apparatus and even machinery – it seems miraculous that Perkin did not blow himself to pieces, taking London’s Ealing with him. In the end, it took two days to create mauve, a process that began with 100 pounds of coal, refined to 10 pounds of coal-tar, then application of naphtha, methylated spirits and aniline, to create a fine black solution which was filtered to powder. However, just one pound of his mauve could dye 200 pounds of cotton.

Detail of The Marriage of Victoria, Princess Royal, 25 January 1858, John Phillip, 1860. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Queen Victoria, inspired by Eugenie, decided to wear mauve to her daughter’s wedding. Soon the whole of London was consumed by what the satirical Punch magazine dubbed the ‘Mauve Measles.’ Perkin’s discovery led to an explosion in synthetic dyes, some discovered by Perkinn and other chemists, others by reverse engineering. Perkin’s mentor Professor Hoffmann released his own violet and black aniline dyes, and in 1861 was hailed by the British Association as the hero of tinctorial science, He returned to Germany, a country that would dominate the new chemical industries.

Knighted for his services, Perkin later described mauve as the “handmaid to chemical science”, having been a preceptor of the staggering, unprecedented growth of the coal-tar industry. In only five years this discovery made Perkin the equivalent of a billionaire, and the intrigues and plots around him would make great TV. He ended up losing much of his fortune to competitors, and aged 35 he sold his company, returned to his makeshift laboratory the attic of the house he now owned, to look for – and find – more colours in the dark.

Queen Elizabeth II © Mirror. Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge

and Princess Charlotte of Cambridge © Getty Images

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense