Blossom Pink | Sense: How colour engages us

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense

Sakura II, 2019 © Andrea Hamilton

“Between our two lives

there is also the life of

the cherry blossom.”

— Matsuo Bashō

On a fine day in 1926, British ornithologist and plant collector Collingwood ‘Cherry’ Ingram wandered from Lake Shoji near Mount Fuji to the town of Fujikawa. He was in search of sakura, and was rewarded in full: the mountain slopes were awash with billowing pink. He wrote in his diary:

Viewed against the dazzling blue of the sky, the trees’ flower-laden boughs seemed as though illumined by a soft glowing light—rosy-hued like the tint of dawn-flushed snow… Here and there, in the pit of the hollows, the eye could make out a nestling, thatched-roofed village, set about with green terraced fields. But the huddled, fantastically steep mountains claimed the landscape, and man was here a mere incident. For long I sat and let the beauty of the scene soak into my soul. – quoted in ‘Cherry’ Ingram: The Englishman Who Saved Japan’s Blossoms, Naoko Abe, 2019.

‘Cherry’ Ingram, Naoko Abe

2019 © Chatto & Windus

Ingram first visited Japan in 1902 on a bird-collecting trip, and became enamoured with the country, returning again in 1907 on his honeymoon, a heady combination of cherry blossoms in full bloom and first love. An avid ornithologist (he was a member of the British Ornithologist’s Club for a record 80 years, dying aged 101), he switched his allegiance to cherry trees, becoming so knowledgeable that in 1926 he was invited back to talk to the sakurakai (cherry society). Exploring with his friend Kiyoshi Suzuki of the Yokohama Nursery, he found to his horror that Japan’s drive towards modernisation, and rejection of feudal society, had deprived the country of hundreds of varieties, excepting the recent hybrid Somei-yoshino, which had become a symbol of national unity and modernity (it is still the most common variety in Japan). Ingram made it his life’s work to restore Japan’s glory.

Cherries grow vigorously across the northern hemisphere in temperate regions: three species in the US, two in Europe and the rest in Asia, but in Japan they are an artform. An emblem of the country itself, they are twisted deep into the psyche: the sakura is also synonymous with samurai, Japan’s lost warrior class. Ingram was almost certainly thinking of this connection when he named one of his cultivars Asano, after the world-famous Forty-Seven Rōnin saga, fictionalised in Japan as Chushingura. After their daimyo (lord) Naganori Asano accidentally insulted shōgun Tsunayoshi Tokugawa’s envoy, and was ordered to commit ritual suicide, 47 of Asano’s samurai retainers, now leaderless and known as rōnin, decided to avenge his death. They planned for a year before pulling off the attack at the envoy’s well- guarded house and after avenging their lord’s death committed hara-kiri or seppuku (lit belly cut).

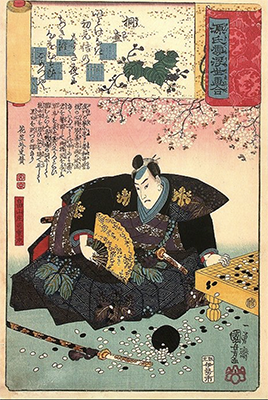

Pawlonia Court, Genjimonogatari Ch.1

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, C.1843. Image courtesy Kuniyoshi Project.

The story holds extraordinary power in Japan because it shows the correct behaviour of the samurai class: to be prepared to die for your lord. Samurai practised bushido – the way of the knight – which was encapsulated by the sakura: we may see pink as feminine in the west but in Japan it is gender neutral and its roots grow far deeper.

The tree spends most of its life quietly growing, establishing itself in any kind of ground, then, for a few short weeks, producing a myriad petals in a dramatic and spectacular display. So too were samurai expected to master the craft of war, carefully nurturing it, then using it for honour in a spectacular display. This sacrifice for greater good is another of the deep precepts of Japanese society: the whole over the self; the samurai’s lives made beautiful by its shortness and their loyalty and sacrifice.

Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms., 2002

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney © University of Chicago Press

This powerful sentiment, that to embrace life is to accept and understand death, could also be used in darker ways. In the last days of World War II, it was utilised by the government to persuade highly-educated students to become kamikaze (lit divine wind) – suicide pilots. Not one professional soldier volunteered: instead 3,843 idealistic young men with no battle experience died for their homeland. In Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization Of Aesthetics In Japanese History Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney describes how they were persuaded that it was an honour “to die like beautiful falling cherry petals” for the emperor. As they readied themselves for death they quoted the famous military poem by the mono no aware scholar Motoori Norinaga:

“Asked about the soul of Japan,

I would say

That it is

Like wild cherry blossoms

Glowing in the rising sun.”

Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka (‘Cherry Blossom’) 2015 © Zbigniew Siwik

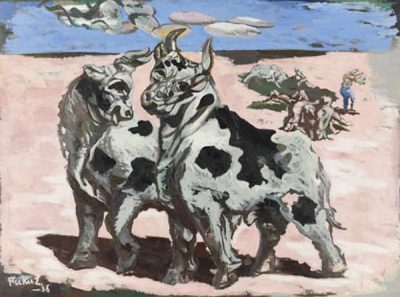

No dissent was tolerated during this time: Surrealist artist Ichiro Fukuzawa, whose sharply satirical works pilloried Japanese society and its rise to nationalism, was imprisoned during the war. In his piece Oxen, two dumb-looking bulls, yoked together, gambol and stamp on a blossom pink ground. Painted in 1936, it was a sharp rebuke to the direction Japan was already taking before it joined the war in 1941.

Oxen, 1936, Ichiro Fukuzawa © The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

A kinder version of Japanese power can be seen in its many gifts of cherry trees across the world, most notably in Washington DC, which, thanks to a gift of 3,000 trees in 1912, has its own thriving hanami scene. One does not need to be Japanese to love what these exquisite blooms stand for.

The cherry blossoms around the Tidal Basin in Washington DC at Sunrise, 1912 © Angela Pan

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense