Chrome Yellow | Sense: How colour engages us

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense

Kusama’s Kabocha, Naoshima Island, Japan 2019 © Andrea Hamilton

On a recent visit to the Benesse Art Site on Naoshima Island in Japan I was struck by how beautiful and playful this oversized pumpkin which is situated at the end of a concrete pier. Yayoi Kusama’s giant yellow pumpkin sculpture hovers over the water like an alien, a pattern of black spots emphasising its tentacled sides. Her pumpkin opus. Surreal octopus gourd. It was the first public artwork to appear on this incredible art island.

It was not her first pumpkin, but an afterimage of the one she painted in 1946, Kabocha (Pumpkin) before leaving Japan. Her first encounter with the vegetable was in a pumpkin patch with her grandfather, who owned a plant seed nursery, “it immediately started speaking to me in a most animated manner… I was enchanted by their charming and winsome form. What appeared to me most was the pumpkin’s generous unpretentiousness.” This would seed to a life-long obsession with the gourd, which she has since described as an alter ego. But it is also her anchor, or rather a portable root, an image she repeatedly returns to for comfort, and magically transports her back to that happy place.

“I love pumpkins because of their humorous form, warm feeling, and a human-like quality and form.

My desire to create works of pumpkins still continues. I have enthusiasm as if I were still a child.”

Interestingly, this links her Kabocha to pumpkins from fairy tales – the one that takes Cinderella to the ball, the head of the Scarecrow Dorothy meets on the yellow brick road – which have the power to take you to where you belong.

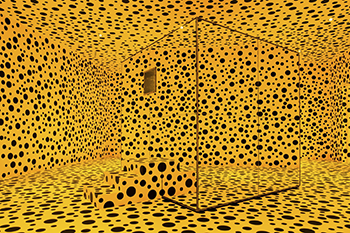

Repetition is key to her process, and arguably defines her whole body of work. Her immersive dotted environments are also a form of after image, taken from the bank of core childhood memories. “A flowery table cloth kicked off her incredible artistic vision,” says Catherine Taft curator and author of the new monograph on Kusama.

She traces the origins of the Infinity Net and polka-dot motifs back to a specific series of hallucinations when Kusama was ten-years-old. “One day, looking at a red flower-patterned table cloth on the table, I turned my eyes to the ceiling and saw the same red flower pattern everywhere, even on the window glass and posts.” This after image effect is well documented by Josef Albers.

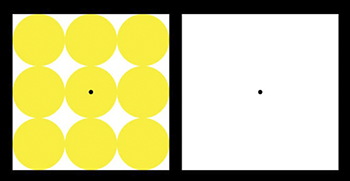

afterimage effect. Interaction of Color by Josef Albers © Brain Pickings

According to Albers, the ‘afterimage effect’ demonstrates the interaction of colour caused by interdependence of colour: On the left are yellow circles of equal diameter which touch each other and fill out a white square. There is a black dot in its center. On the right is an empty white square, also with a centered black dot. Each is on a black background. After staring for half a minute at the left square, shift the focus suddenly to the right square. Instead of the usual color-based afterimage that would complement the yellow circles with blue, their opposite, a shape-based afterimage is manifest as diamond shapes — the ‘leftover’ of the circles — are seen in yellow.

The polka dot yellow pumpkin is to Yayoi Kusama what the sunflowers were to Vincent Van Gogh, or the banana to Andy Warhol, a natural form that reflects how she perceives the world. Her work highlights the fine line between obsession and madness. Kusama, who has struggle with mental health illness since childhood, developed coping strategies by using her hallucinations and obsessive pattern making. They are both subject and outlet for her prolific artistic outpouring. Her art practice might be seen as a survival mechanism, one in which she processes her hallucinations by looking deeply into them. The works could be seen as a confrontation of phobias – black and yellow combined usually signals danger/ stay away in nature – and their power lies in her courage to make sense of the alternative reality her mind perceives.

Yayoi Kusama

: in infinity, Louisiana museum of modern art 2010 © Kim Hansen

“The room, my body, the entire universe was filled with it, my self was eliminated, and I had returned and been reduced to the infinity of eternal time and the absolute of space. This was not an illusion but reality… I ran for the stairs… I saw the steps fall away one by one, pulling my leg and making me trip and fall… I sprained my leg. Dissolving and accumulating, proliferating and separating. A feeling of particles disintegrating and reverberations from an invisible universe.”

For the viewer however, it’s a chance. Immersive works like this can literally change your mindset: engaging all your senses, they create powerful memories that influence us in the most unexpected ways, with the most unlikely connections.

Like Cristo and Jean Claude’s gargantuan coloured environments, and Georges Rousse’s trompe l’oeil, we feel connected to the mind of another, and so more accepting of our own. Great works of art are often hewn from deep wells of pain or insecurity, Van Gogh who could not even afford a model to sit when he decided to paint at 27, created 37 self-portraits with a mirror – a unique catalogue of raw emotion equal to Rembrandt’s self-portraits.

Yayoi Kusama, Photo: courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, David Zwirner, New York, and KUSAMA Enterprise © Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama 2017 © Phaidon

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense